theotherbeaver.com

Online Community News for Lumby, Cherryville, Rural Coldstream and Highway 6

The Rendezvous Chronicles

150 Years as British Columbia

Don Elzer tells a story of what the ancient landscape of the Okanagan and the Monashee may have been like as the last great ice age began to retreat. This is a speculative account however there is new scientific evidence surfacing that sheds new light on the fantastic changes that occurred here 15,000 years ago.

A Mystery Unfolds:

An ancient inland sea soon

exposes a new world in the

Okanagan and Monashee

The southcentral interior of British Columbia is rich in natural history, in particular the Okanagan Valley as it links north to the interior plateau and east to the Monashee Mountain range.

In this region geological history unfolds beginning with a torrent of molten lava caused by eons of volcanic activity.

VOLCANIC TURMOIL

Along the eastern edge of the Okanagan are the Monashee foothills which have within them part of a volcanic field made up of numerous, small, basaltic volcanoes. Individual volcanoes have been active for at least the last 3 million years during which time the region was covered by thick glacial ice at least twice.

Volcanic eruptions underneath and through the thick blankets of glacial ice produced numerous unique glacial volcanoes and deposits, which may have occurred during the initial formation of both the Camels Hump and Bluenose Mountain.

These sub glacier volcanic eruptions and surface eruptions between the periods of glaciations, filled river valleys with many layers of basaltic lava flows and deposited the tertiary series of rocks that we find today.

It’s unknown just how active lava flows had become 20,000 years ago but today we can find evidence of this spectacular activity that goes back millions of years.

The Camels Hump, Bluenose and Saddle Mountain display ancient basaltic flows. Basaltic lava shrinks as it cools and forms vertical columns such as those found near Dennison Lake south of Creighton Valley. Rows of rock like those found on Layercake Mountain above Galaghers Canyon in Kelowna can peal off the cliff face like slices of bread, preserving the vertical nature of the cliff. The lava would most certainly cool as ice became the next resident that would begin to sculpt the landscape off and on for sixty thousand years.

THE LAST ICE AGE

Throughout the earth's history the climate has fluctuated and at times the temperatures have been cooler than they are today. This change in temperature can last somewhere between 2-10 million years and is referred to as an ice age.

During an ice age the snow begins to accumulate at higher elevations, and in the mid to upper latitudes. Due to the cooler temperatures during the ice age, the snow does not completely melt during the summer months. The snow continues to accumulate, compacting under its own pressure and forming glaciers that flow like slow moving rivers of ice down the valleys and into the plains, spreading out across vast parts of the continent.

There have been at least five major ice ages in the past one billion years. The most recent, the Pleistocene Ice Age, began about 2 million years ago. Glaciers did not continually cover the earth during this time; there have been interglacial periods where temperatures warm slightly and the glaciers melt and retreat.

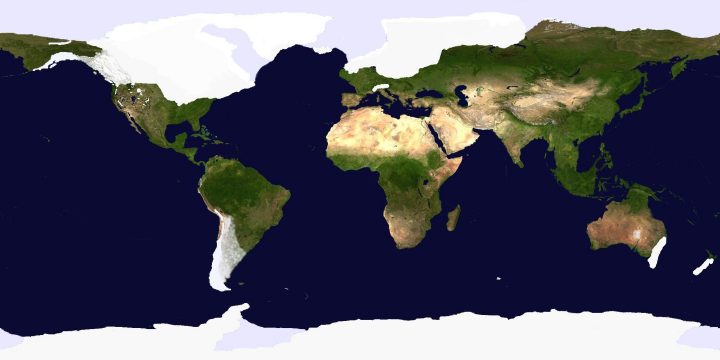

In the most recent advance, these sheets of ice and snow covered British Columbia and reached their maximum extent 15,000 years ago and had almost completely melted by 10,000 years ago.

Ice sheets 3-4 kilometres thick covered this region very similar to the polar ice cap that we know today.

The ice reached from what is now the Yukon in the north to the 40 degree parallel in the south. It reached into the Pacific Ocean in the west, to the eastern slope of the Rockies where at times an ice-free corridor formed, where the Canadian prairies lay today.

MELTING ICE

Just over 15,000 years ago the last great ice age that had completely covered the interior of British Columbia was beginning to quickly recede, which once again caused our landscape in the Okanagan and the Monashee to change.

As the ice melted, water drained into catchment areas forming torrent rivers and huge lakes. These events may have created a narrow ice-free corridor that stretched from the Yukon through mountain passes and then along what we know as the Great Interior Plateau.

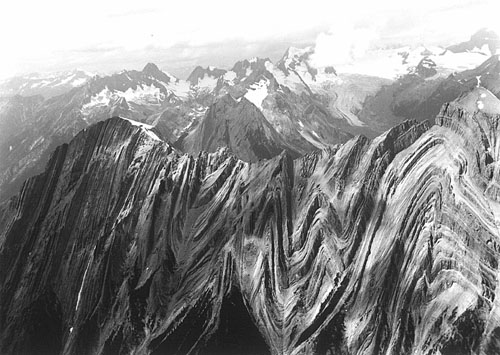

We could maybe assume that this region was on the cusp of a declining glacier that covered the Monashee mountain range. As the glacier retreated we could maybe imagine the upper reaches of the Shuswap River as a river the size of the Columbia or the Fraser, spanning across the entire width of a valley. Mable Lake would simply be part of this very large river meandering through a newly carved river valley.

The upper Shuswap River would have raging creeks and waterfalls draining a vast ice field, with a similar landscape as that of the Columbia Ice Fields today.

Connecting rivers or streams to the Shuswap, like Bessette, Duteau or Monashee may have been torrents of water tumbling down jagged ravines carved out of steep rock cliffs at the edge of the great glacier as it still covers most of the peaks of the Monashee Mountains.

The Blue Springs Valley between Lumby and Cherryville may have been part of a deep lake, which joined a large inland sea to the west. Around the perimeter would be old volcanic vents like the Camels Hump which would emerge as rocky islands not far from the shore.

To the east would be the beginning of a plateau, which we know as the Greystoke, Aberdeen or the Okanagan Highlands that would gently meet the sea. The shoreline would reach for many miles to the south and to the east to the foot of the Monashee and the ice fields. On this plateau we would find sand dunes and loose stone surrounded by the remnants of more ancient lava domes.

OPENING OF A CORRIDOR

Over a long period of time this thin edge of land may have expanded further in a north south direction. The planet warming along with volcanic activity beneath the surface of the earth may have accelerated the melting of the ice fields in what is now central British Columbia. On each side of the corridor would be a wall of ice, which would feed water into vast catchment areas.

There may have been earth tremors, quakes and volcanic vents steaming the landscape. The corridor was often a treacherous environment as the climate warmed, ice breaking from the glacier could create ice dams, which would cause flooding and divert water channels. In places this corridor would have remained narrow and inconsistent until it reached large plateau areas of land, and may have also disappeared completely into the great sea.

These large seas or glacial lakes may have been in existence for thousands of years allowing ecosystems to develop and flourish around them, and within any land corridors that may have existed.

ANCIENT HABITAT

The climate 15,000 years ago was beginning to warm and began to create a lush environment for plant life to thrive. Such an environment would have stayed relatively consistent for nearly 10,000 years as the last great ice age slowly subsided.

We can only speculate of the habitat that makes up this corridor of land. Melting glaciers were causing the climate to become more moist but there would still be chilly winds and cold fronts coming off of the glacier areas. But the climate was cool and mild with significant rainfall, which caused some forms of vegetation to thrive.

Such a corridor may have consisted of a mix of woodlands and grasslands with most of the land being soggy and moist. Pine, spruce and tamarack makeup the forest that is carpeted with grass. There are grasslands with a vast number of ponds and bogs.

If one could imagine the upper reaches of the Monashee foothills and the Okanagan plateau areas as lush and park-like. There would be much less erosion present than today, and a much higher water table with marshlands and lakes covering what is now valley bottom areas.

GREAT LAKES AND A GREAT FLOOD

During that time most historians have agreed that about 15,000 years ago there where at least three great lakes that formed in the western part of North America. These were huge as catchment areas for great amounts of water caused by the melting of the huge glacier that was nearly equal in size to a polar ice cap.

Lake Missoula which covered what is now Montana; Lake Bonneville which covered parts of Nevada and Utah; and Lake Agassiz a vast lake covering much of Manitoba and western Ontario (almost the size of the Yukon) were three large lakes that would each be larger in size to any two of the Great Lakes of today.

According to many researchers the last ice age covered the entire area west of the Rockies, however there may be recent evidence that as the ice sheets melted, certain land corridors were exposed creating new lakes, possibly one in southern BC.

This fourth great glacial lake may have covered much of the south central interior of British Columbia including the Okanagan Valley. This great sea of water may have stretched from Wells Gray Park to the Canadian/US border.

While this lake still remains a theory, lessons can be learned from studying a similar ancient lake that was formed as a result of the last glacial advance that moved south through the Purcell Trench in northern Idaho, near present day Lake Pend Oreille, damming the Clark Fork River thus creating Glacial Lake Missoula.

The water from the melting glacier began to build up behind the 900 meter high ice dam, which filled the valleys to the east with water, creating a glacial lake the size of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario combined. The water continued to rise until it reached its maximum height at an elevation of about 1500 meters. As the water rose, the pressure against the ice dam increased, ultimately, causing the dam to fail. The failure occurred when the water reached a depth of 700 meters. The water pressure caused the glacier to become buoyant, and water began to escape beneath the ice dam by carving sub-glacial tunnels at an exponential rate causing a catastrophic event of planetary proportions.

It is estimated that water moving at speeds of 120 kilometers per hour raced across eastern Washington at a volume 60 times the flow of the Amazon River, the largest river in the world today. At this rate, the lake probably drained in a few days to a week.

The floodwaters from Glacial Lake Missoula moved through eastern Washington on a 430-mile journey to the Pacific Ocean, forever changing the landscape by stripping away topsoil, and picking apart the bedrock. The floodwater carved an immense channel system across eastern Washington.

In 1928, geologist J. Harlen Bretz poetically described the scene: "No one with an eye for land forms can cross eastern Washington in daylight without encountering and being impressed by the 'scabland.' Like great scars marring the otherwise fair face of the plateau are these elongated tracts of bare, or nearly bare, black rock carved into mazes of buttes and canyons. Everyone on the plateau knows scabland. It interrupts the wheat lands, parceling them out into hill tracts less than forty acres to more than forty square miles in extent. One can neither reach them nor depart from them without crossing some part of the ramifying scabland. Aside from affording a scanty pasturage, scabland is almost without value. The popular name is an expressive metaphor. The scablands are wounds only partially healed over the underlying rock which nature still protects."

BRITISH COLUMBIA’S GREAT INLAND SEA

The distinctive cliffs and terraces seen in the south Okanagan are one very obvious example of the landscape being formed by sand, silt and gravel deposition and shaped, to some extent, by melt water from the receding glacier.

This was indeed an Earth alive and changing, but here too, something was about to happen about 15,000 years ago, perhaps in a single day, perhaps over a few hundred years.

A series of quakes would shake at the north end of the great sea near what is now Wells Gray Park, causing a tetonic plate to shift and place extreme pressure on the entire catchment area that was already under pressure from increasing amounts of water draining into it from melting ice sheets.

The natural dam on the south end of the sea would burst causing the huge body of water to drain in one single cataclysmic event. This torrent of water would carve out the landscape much the same way Lake Missoula did.

As the water dissipates a new landscape emerges, barren and muddy, but one that displays the characteristics more familiar to us today.

New and fantastic scientific discoveries about a megaflood in the Okanagan

(30)

In a UBC Report by Bud Mortenson published in April 2007 he explained a theory by Robert Young an Assoc. Prof. of Geography and Earth and Environmental Sciences at UBC Okanagan that indicates that a great body of water formed over the Okanagan Valley as a result of melting ice sheets.

Young’s theory goes even farther, with new evidence suggesting an Ice-Age megaflood that created Washington State’s Channeled Scablands about 15,000 years ago partly originated in south-central British Columbia, not exclusively from Montana as the prevailing theory suggests.

The megaflood’s statistics are staggering. Arriving from the northeast, a wall of water tall enough to leave gravel bars 120 metres high ripped across Washington at 120 kilometres per hour, eroding more than 80 cubic kilometers of earth and rock in two or three days. The torrent left a scoured 25,000-square-km landscape riddled with deep canyons -- known as coulees -- carved out of the hard bedrock.

“The question of where all that water came from has been hotly debated for decades,” says Young. Most think the floodwater came from Glacial Lake Missoula, 400 kilometres away in Montana. As big as Lake Ontario and Lake Erie combined, Lake Missoula was held back only by a dam of ice near the Montana-Idaho border. The long-held hypothesis is that when the ice dam broke, the water poured westward with unimaginable fury and destruction.

Lake Missoula breaching its ice dam may have been impressive, Young says, but probably not impressive enough to account for the Scablands. “Models of dynamic hydrology suggest that floodwaters from the Missoula Basin alone were insufficient to fill the Scabland coulees, much less do all of the work required to produce the incredible landscapes in the region.”

Instead, Young is looking for a water source from the north, where the massive Cordilleran ice sheet covered much of British Columbia. His attention is on a lobe that buried B.C.’s Okanagan region beneath nearly three kilometres of ice, terminating almost on top of the Scablands south of the Okanagan.

A cataclysmic chain of events originating under this southern B.C. ice, perhaps triggered by volcanic eruptions from below and surface meltwater making its way through the immense ice sheet, would change prevailing theories about one of the greatest flash floods of the last Ice Age.

“The Okanagan and surrounding uplands are part of dramatic landscapes, including landforms carved into bedrock like the Channeled Scablands,” Young says. “Features such as water-eroded channels that can go uphill, and streamlined landforms caused by fluids flowing turbulently at high velocities, all suggest huge flows came out of the Okanagan Valley and drained south into the Columbia drainage.”

He argues that massive volumes of melt water flowing under the Okanagan ice pushed southward -- probably along more than one path. Part exited from the southernmost point of the ice sheet, purging into the Scablands.

More water rushed southeast down the southern Rocky Mountain Trench into Glacial Lake Missoula, and under glaciers emanating from the Purcell range. When the ice dam at Glacial Lake Missoula failed, floodwaters spilled west several hundred kilometres into the Scablands hours or days after the initial onslaught.

Young says the challenge is that, until only recently, sub-glacial reservoirs have not been considered candidates for the kind of catastrophic flooding that created the Scablands.

However, there’s evidence today that huge volumes of water do collect under ice sheets and are released in outbursts of flooding. “Movement of large water volumes of melt water beneath the Antarctic ice sheets have been reported by several researchers in the last few years,” Young points out. “And in Greenland gigatons of water on top of ice sheets have been observed draining through the ice very quickly -- in as little as 48 hours.”

Over several years, he says, water accumulates under the ice and eventually it can lift or “decouple” the ice and flood through any exit it finds. “In Iceland, this process occurs regularly, and is greatly accelerated when intermittent sub-glacial volcanic eruptions occur, causing the reservoir to overfill, and leading to flows many times those normally seen during regular outburst floods,” Young says.

There’s evidence of volcanic eruptions beneath the ice sheet just north of the Okanagan -- in what today is B.C.’s Wells Gray Provincial Park. “Many of the deposits and volcanoes there bear telltale marks of sub-glacial eruption, including pillow basalts on mountainsides and flat-topped volcanoes,” Young says. “Volcanologists studying the region indicate that three volcanoes erupted sub-glacially during the last glaciation.”

Volcanic activity and normal surface melting could eventually produce enough water to decouple the overlying ice and drain catastrophically, says Young.

“With no other sufficient source of water for the Scablands megaflooding, and equipped with several realistic mechanisms for water formation,” he says, “we must consider the Okanagan scenario as a valid alternative to Lake Missoula alone accounting for such a catastrophic event.”

So the question remains, was the great sea a submerged one covered by a thick layer of ice, or had the ice melted forming a much warmer environment in this ancient region?

Had this acient Okanagan lake actually triggered the Great Missoula Flood?

Was McIntyre Bluff near Okanagan Falls the site of a giant ice dam?

Perhaps the historical data has yet to be discovered to give us clear answers. But ancient seashells and coral along the edge of a tiny lake between Lumby and Cherryville may provide further clues about this ancient landscape as well as its first inhabitants.

(30)

SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERY

An Ancient Glacial Lake in the Okanagan

What proof do we have of an extraordinary megaflood in the Okanagan?